Pricing Experiments You Might Not Know, But Can Learn From

Lots of entrepreneurs struggle with pricing. How much to charge? It’s clear that the right price can make all the difference—too low and you miss out on profit; too high and you miss out on sales.

Don’t ask, can’t tell: Asking people what they’d pay for and how much rarely works. [Tweet it!]

For one thing, people will tell you what they want to pay—which is obviously much less than what your product or service is actually worth. Second, what people say they would do and what people end up doing are very different things.

When it comes to money, people are unable to predict accurately whether they’d pay or not. It’s much easier to spend hypothetical dollars than real ones.

Also, it’s worth remembering that people really don’t know how much things are worth or what’s a fair price (which is the reason TV shows like “The Price Is Right” can actually exist).

People tend to be clueless about prices. Contrary to economic theory, we don’t really decide between A and B by consulting our invisible price tags and purchasing the one that yields the higher utility. We make do with guesstimates and a vague recollection of what things are “supposed to” cost.

People are weird and irrational, and there’s much we don’t understand. For example, why do shoppers moving in a counterclockwise direction spend on average $2.00 more at the supermarket?

Why does removing dollar signs from prices (24 instead of $24) increase sales?

What will work for you depends on your industry, product, and customer. When you try to replicate what Valve did to increase their revenue 40x, it might not work for you, but then again, why not give it a try?

Here’s a list of pricing experiments and studies you can get ideas from and test on your own business.

Note: CXL Institute has original research on SaaS pricing pages. Find out how you should order your pricing plans to generate the most revenue, and what happens when you highlight a “recommended” plan.

Table of contents

- The Economist and decoy pricing

- The magic of number 9

- Is there anything that can outsell 9?

- Anchoring and the contrast principle

- Anchoring

- Anchoring influences prices

- Straightforward pricing

- Pay what you wish

- Suggested price

- Well-known PWYW examples

- Combine “pay what you wish” with charity

- Offering three options

- Price perceptions

- Context sets perception

- Can I split test the price?

- Combine research from this article

The Economist and decoy pricing

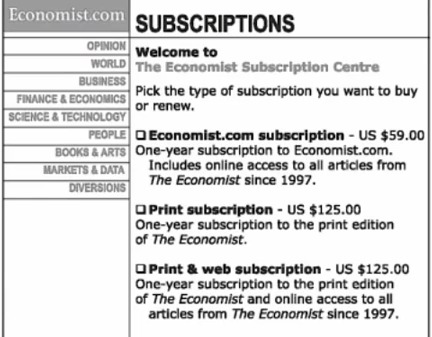

Dan Ariely describes this famous example in his amazing book Predictably Irrational. He came across the following subscription offer from The Economist, the magazine (he’s also explaining this in his TED talk

Both the print subscription and print & web subscription cost the same, $125 dollars. Ariely conducted a study with his 100 bright MIT students. In it, 16 chose option A and 84 chose option C. Nobody chose the middle option.

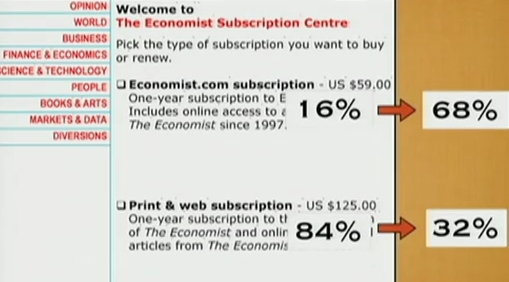

So if nobody chose the middle option, why have it? He removed it, and gave the subscription offer to another 100 MIT students. This is what they chose now:

Most people now chose the first option! So the middle option wasn’t useless, but rather helped people make a choice. People have trouble comparing different options, but if two of the options given are similar (e.g., same price), it becomes much easier.

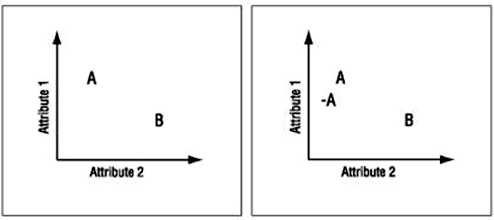

The same principle was used with travel packages.

When people were offered to choose a trip to Paris (option A) versus a trip to Rome (option B), they had a hard time choosing. Both places were great—it was hard to compare them.

Now they were offered three choices instead of two: trip to Paris with free breakfast (option A), trip to Paris without breakfast (option A-), trip to Rome with free breakfast (option B). Now overwhelming majority chose option A, trip to Paris with free breakfast. The rationale is that it is easier to compare the two options for Paris than it is to compare Paris and Rome.

A graph to describe this: